#Letstalkaboutmentalhealth

|

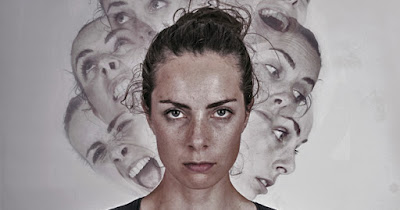

| Credit: Natural Health News |

My clever, sassy, witty, vibrant, sociable, warm, feisty, feminist, artistic, beautiful Daughter No 2 has been diagnosed with Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder.

She rang me after her Adult Mental Health Services appointment in tears. I was sipping a cappuccino in Marks and Spencers which went cold before I finished it. I muttered something about “it’s only a label”, and “this is still a really new area of medicine”, but the truth was I didn’t know very much about the term. Mrs A had a similar phone conversation at about the same time.

We weren’t expecting this diagnosis. Neither was Daughter No 2. Her mental ill health had become more apparent over the preceding year and she had been seen, in hap-hazard fashion, by the county Children and Adolescent Mental Health Service, known as CAMHS. As we did, Daughter No 2 believed – hoped – that the anxiety, depression, panic attacks, recklessness and manic behaviour which were afflicting her on a regular basis were a ‘phase’; that the symptoms would pass. However, Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder, EUPD, is not a ‘phase’, we learned from Google later that day. It is a life-limiting condition.

The first inkling we had about the extent of her declining mental health was about 18 months ago when she came back from the Doctor’s having been prescribed Citalopram. ‘A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor’, it said on the box. That’s an anti-depressant and panic attack reducer, to you and me.

Nearly one in four young women has a mental illness, with emotional problems such as depression and anxiety the most common. An NHS study recently found young women aged 17 to 19 were twice as likely as young men to have problems, with almost 24% reporting a disorder. Body image pressures, exam stress, home life and the negative effects of social media are all thought to affect girls disproportionately.

Despite these stats, which are becoming increasingly widely recognised, I was resolutely displaying all the classic signs of denial. And let’s be clear. This is a blog about me. About how parents struggle to accept, process, deal with and live through the mental health needs of their offspring.

The pretext for DN2’s initial visit to the GP was to tackle disruptive sleeping patterns. Storm in a tea cup, we said. Just get into a regular routine and sleep will come. “And turn off the bloody phone*/TV*laptop* (delete as appropriate) before you try to go to sleep…”

The lack of sleep was real. But it was a symptom of a more serious malaise; and also served as a smokescreen for her visits to the Doc’s. The smokescreen was successful in obfuscating uncomfortable questions and unwanted advice from parents. Buying enough time until she could unpick some of information that would come through from the professionals.

Apart from a realisation that DN2 was much more ill than we realised, this period also emphasised two other points which later became a pattern.

First - she wanted to be well. By self-diagnosing from the web and from within her peer group, DN2 knew she was more ill than she was letting on to us. Even through the dark times, when as parents, Mrs A and I are sick with worry and sleepless with fret, we know she desperately wants to do something about it.

Second - she was driving the process. As loving, caring, worrying parents with our daughter’s absolute best interests at heart, we found ourselves disempowered. We were not making the decisions and we were often not her first port of call for support. Some of her friends had similar symptoms of their own and and were better placed to offer an unconditional, informed ear.

Neither was I accepting of the realities. I was shocked when she came back from the GPs after a full mental health assessment with a rattling bag full of powerful drugs. Both Mrs A and I were scathing of the medical profession that would prescribe them. I was still banging on about lifestyle changes and mindfulness approaches. It was only when we sat down and listened to her – and it was not easy getting to that point – that I recognised the doctors had been pretty comprehensive in assessing her risks. They had not prescribed this stuff willy-nilly. They were part of a treatment plan reacting to her chilling responses in a detailed diagnostic mental health assessment.

As a Dad, it is hard to describe the stabbing despair of seeing your youngest daughter come down to breakfast with multiple razor cuts on her arms, or gouges on the back of her hand. Except to say that every slice and gash hurts me nearly as much as it does her. In some ways that is the point. In the dark and demon filled nights, self-harming is often seen as a way of releasing overwhelming emotions; a way of getting them outside. Mostly she doesn’t want to talk about it, but when she does, there is a sense that the physical pain of self-harm is easier to deal with than the emotional pain that's behind it.

When she is having a panic attack, and I look in to her eyes, I see real fear. Fear about losing control, about what she might do to herself, where it might all end. That’s where the worry comes from. Kicking straight back into the parenting mode, my thoughts are “what if I’m not there to help, to prevent, to divert”. Such thoughts are futile but inevitable.

Or the simple pain that comes from knowing that she has been crying all day.

We are a bit better about reacting to her periods of panic and fear now. Sometimes - though not always - Daughter No 2 will ask for help when she is tipping over the edge. One long and disturbing evening quite early in the journey proved to be a bit of a watershed in the way we all began to deal with the situation. Daughter No 2 came back from the pub in the midst of a panic attack, sobbing wildly and highly distressed about how she “couldn’t take it any more, I just can’t do it”. There was something here about feeling like an under achiever and relative comparisons, expectations and achievements within a large peer group.

But right then, that was not the immediate concern. She was at the end of her tether and wanted to go into hospital for a psychiatric assessment. This did not feel like the right step to Mrs A and I. DN2 had been given a helpline number by CAMHS and so together we gave it a try. What became clear was that there was no viable support network in place. Through protracted, dysfunctional phone calls with a series of out of hours services, the best offer was for DN2 to check in to A&E. At 11pm on a Saturday night. No thanks.

Mrs A, my daughter’s boyfriend and I sat up with DN2, talking and not talking, for as long as was needed. Several runs of ‘Despicable Me’ later, DN2 was calm and back in control. She went to bed and was close to ‘normal’ the next morning. Families and extended networks have a real role to play.

After several months, DN2 was referred to Adult Mental Health Services. In talking to other parents in similar situations, it seems we have been lucky. Many young adults slip through the yawning gaps between juvenile and adult services, leaving parents frustrated and bereft. This is often because the onus for action switches to the young adult. Parents can no longer drive the engagement. A subtlety we did not immediately grasp, given that our daughter had taken the initiative from the start.

We later discovered that CAMHS had made a provisional diagnosis of emotional personality disorder some time before her last contact with the service. The diagnosis remained provisional because only adult services could confirm this and sanction therapeutic responses, rather than counselling. So there had been months of treading water.

The diagnosis is a controversial one. There is a raging debate about how helpful the description of personality disorders really is. I find myself persuaded that the focus should instead be on what DN2 needs so that she can deal with her problems, not what category she is in or what stigma to attach to her. Even the term ‘personality disorder’ sounds judgemental.

My daughter now has regular therapy sessions, and they seem to be helping. She has a trustful relationship with her therapist who is encouraging coping strategies and healthy behaviours which will help to break down dissociation and the closing out of emotions and feelings; interrupting the erratic cycle of mania, depression, introspection and stability.

There are plenty of potholes, rocks and blind bends on the road to recovery though. And I’m talking about the responsible parenting thing again. I’ve learned that I’m not as immune to what other people think as I’d hoped. I can become very defensive when anybody criticises my daughter. Once, when this negativity came from a friend, I had no hesitation in cutting them out. As far as I was concerned, they were not trying to offer constructive support, but were making shallow judgements based on flippant observations - almost entirely on physical appearance – which were incredibly damaging. “Oh, I saw your daughter the other day. All those piercings and the hair colour. Sad really, she looks so hard.” This is mostly ignorance, rather than a desire to hurt. But still. (You may be able to detect that my approach to all this is still a work in progress… )

I’ve also learned that if DN2 doesn’t want to discuss things, there is no point pushing for answers. She still closes down very effectively when needed, despite the best intentions of the therapist. We’ve had rows of course. When frustrations bring difficult issues to the surface and heighten tensions within the family. Most often these issues highlight the clash between ‘old fashioned’ views about what recovery should look like and current understanding that recognises how depression impacts on motivation and creates barriers to achieving goals that others would consider minor.

There remains a lot of ignorance. I recognise the all too easy temptation to reach for epithets like “pull your socks up”, “just get on with it”, “We never had this in our day. We just had to deal with it.” These views have led to a lot of undiagnosed mental illness and grief over many years. I believe and hope that we are moving on from that. There is something of that spirit in this blog post. A path made possible by the brave words of earlier pioneers in similar circumstances.

This where I trot out the hackneyed old metaphor about the rollercoaster ride we have all been on this last 18 months. Right now, we are still in the car, clinging to the guard rail and peering down the tracks in the vain hope of picking out the next twist. But we are absolutely there for her, when she needs us, every minute of the ride.

My daughter and I have talked about this blog and she endorses it.

“It’s sad”, she said, “It isn’t going to be a fun read for anyone, lol!”

“Dunno”, I replied, “It’s like car-crash TV innit? Ha!”

Comments